“Great investors are those who are generally less affected by cognitive bias than the general population, learn about biases and how to cope with them, and put themselves in a work environment that allows them to think well.”

Thorsten Hens and Anna Meier of Behavioral Finance Solutions

Behavioral finance posits that asset prices are affected by investors’ emotional and cognitive biases, as well as financial factors. The behavioral approach to finance has garnered significant attention, especially after Richard Thaler won the 2017 Nobel Prize in Economics for his work on how people are “predictably irrational.”

At LNW, we believe awareness of emotional and behavior biases can improve investment outcomes and we have incorporated the basic tenets of behavioral finance into how we evaluate the asset managers we use in client portfolios, and ultimately, how we make investment decisions. This paper focuses on two things:

- What behavioral biases in investing look like;

- How LNW identifies these biases in asset managers and also within our own investment team, so we can mitigate the impact on our investment decisions.

The Basis for Behavioral Finance

Traditional finance theory presumes investors are rational, fundamentally risk-averse, and get diminishing levels of “utility” (satisfaction) from incremental increases in wealth. Therefore, as wealth increases, the willingness to take on risk decreases. While all that sounds plausible, it includes a number of faulty assumptions:

- All investor choices and preferences are known.

- The relative attractiveness of investments can be ranked consistently.

- The utility of investments (the level of satisfaction) is additive and can be quantified.

- The point of change in investor attitudes (aka “indifference”) can be accurately quantified.

To compensate for the above shortcomings, academics like Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky proposed Prospect Theory, which is the basis of behavioral finance. Prospect Theory postulates that the biggest impact on investor behavior is the magnitude of investment losses, not losses per se. Assumptions of this theory include:

- Investors focus on changes in their wealth, not their actual level of wealth.

- Gain or loss is viewed from a reference point, often the year-end price or original cost.

- Gain or loss is actualized only after an investment is sold.

- Low-probability events are given too much weight (i.e., investors like to believe that something can happen, even though there may be a slim chance of it happening).

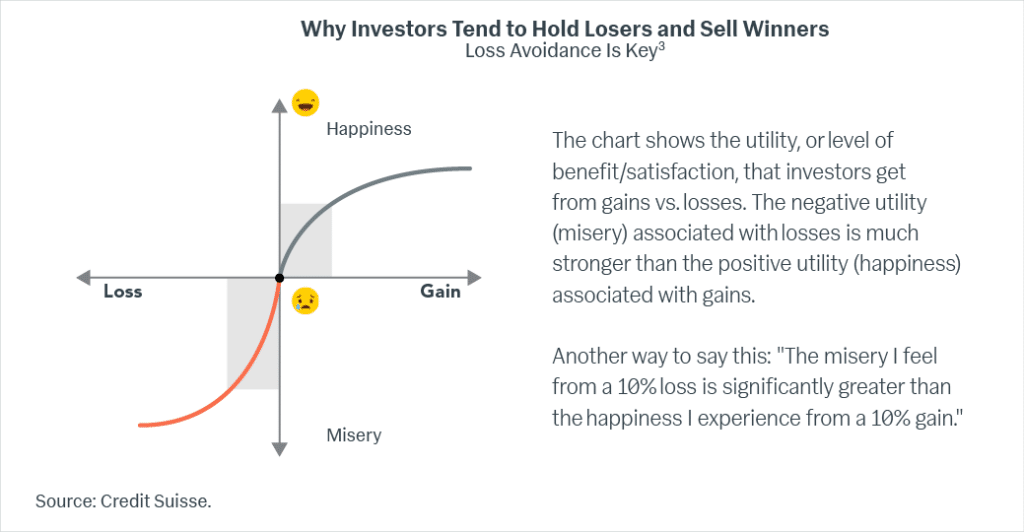

Prospect Theory counters traditional finance theory by postulating that investors, regardless of their level of wealth, are highly sensitive to losses and alter their behavior to avoid having to realize them, sometimes regardless of the true costs. The overemphasis on loss avoidance often leads to mutually reinforcing and damaging outcomes: (1) selling stocks or other assets with significant gains too soon, fearing they will lose value; and (2) holding on to stagnant or depreciating stocks too long, hoping for a rebound (and not having to realize a loss).

Another name for the above loss-avoidance behavior is the “disposition effect.” As investment analysts at LNW, we have observed the disposition effect when assessing and reviewing equity managers. This is what happens when an asset manager has incorrectly assessed the outlook for a stock or other investment yet continues to hold it in order not to concede defeat. In many cases, the manager presents an overly optimistic picture of the company’s prospects as rationale for maintaining the position. This can lead to additional losses, as well as the opportunity cost of not investing in better risk/reward opportunities.

Investors’ difficulty in making optimal decisions relates to what economist Herbert Simon referred to as “bounded rationality.” Simon comments that “rationality is limited by the available information, the tractability of the decision problem, the cognitive limitations of the mind, and the time available to make the decision.”

Essentially, as humans we have limitations regarding the volume of data we can process. Additionally, we are molded by our individual experiences, which may lead us to not always act rationally. A basic example of this is seeing a roulette wheel land on black numbers five times in a row, you might then expect the next number to be red or green, even though the probability remains the same between black, red and green.

Bounded rationality theory holds great implications for traditional financial theory. That’s because it assumes that investors are not able to make rational decisions consistently. Instead, investors “satisfice,” or accept the most satisfactory option based on the available information and prior experiences.

Recognizing Cognitive Limits and Emotional Bias

There are two main types of bias: cognitive and emotional. The investment team at LNW attempts to identify these biases in the asset managers we assess and invest with, while being cognizant of how these same errors can manifest in our own views and recommendations.

Cognitive errors result from faulty reasoning. Some of the most common cognitive errors:

- Conservatism Bias: Failing to update your view after receiving compelling new information.

EXAMPLE: An asset manager learns that a company whose stock he owns is doing something unusual — acquiring a business in a totally different industry — but he doesn’t question this given that he’s known the company executives for a long time and these same executives have consistently made good decisions. - Confirmation Bias: Looking for and/or utilizing only the information that confirms your view while disregarding conflicting data.

EXAMPLE: A research analyst doing due diligence on a company is pressured to provide an investment idea for the portfolio. The analyst finds more evidence that confirms their thesis while ignoring evidence that contradicts it. - Representative Bias: Assessing new information based on past experiences.

EXAMPLE: A portfolio manager with many years of experience in the materials sector overemphasizes supply/demand dynamics in evaluating companies, even though other differentiators may be more important, such as innovation and technology. - Illusion of Control Bias: Thinking that something will happen because you are convinced it will, even though you have little or no control over the ultimate outcome.

EXAMPLE: A portfolio analyst thinks she has found a greatly undervalued stock and urges buying it right away, only to have it go nowhere for years. - Hindsight Bias: Focusing only on your good calls and ignoring your bad calls. This can lead to an overestimation of capabilities and not learning from past mistakes.7

EXAMPLE: A equity manager has overweighted both healthcare and technology in portfolios. A year later, she talks up the 20% gain in tech while downplaying the 25% loss in healthcare. - Anchoring and Adjustment Bias: Focusing on a single data point and actively discounting new information that counters it.

EXAMPLE: A portfolio manager finds a stock with an extremely low price-to-book value ratio and buys it, ignoring that the company’s plant and equipment may be virtually worthless given recent market developments. - Mental Accounting Bias: Thinking that something can be controlled by segmenting and categorizing, instead of looking at it holistically.

EXAMPLE: An asset manager maintains 60% of her fund in relative-value stocks; 30% in deep-value stocks, and 10% in special situations to diversify and thus lower risk. While this may be a reasonable approach, it does not actually address overall risk in the portfolio. - Framing Bias: Allowing how information is presented to affect how you understand it.

EXAMPLE: An asset manager may think the management of a certain company is more competent or capable since they present data in a more interesting way, even though the presentation itself masks negative metrics. - Availability Bias: Thinking that the latest available information is more significant.

EXAMPLE: A portfolio manager decides not to sell certain stocks based on a Wall Street Journal article that U.S. housing starts are at their highest point in five years, without considering the reason why that’s the case: where we are in the economic cycle, level of interest rates, etc.

Emotional errors arise from personal feelings and are manifested subconsciously, making them the hardest to realize and combat. For investors, the most challenging emotional errors are:

- Loss Aversion (Prospect Theory) : Focus on avoiding losses, regardless of true cost.

EXAMPLE: To avoid realizing losses, an asset manager sells his winners too soon (losing out on future price appreciation) and holds on to losers too long, expecting them to recover eventually, without considering opportunity costs. - Overconfidence (Illusion of Knowledge): Thinking you know more than you do.

EXAMPLE: An asset manager may think he has discovered something that other investors have overlooked or not fully realized and “priced-in.” This usually leads to overconfidence and overly optimistic/pessimistic assumptions. - Self-control: Emphasizing short-term results over long-term goals.

EXAMPLE: An asset manager may take on more (or less) risk at certain times, veering away from portfolio targets, for performance or other reasons. - Status Quo: Getting complacent about what you currently own.

EXAMPLE: An asset manager decides not to seek better risk/reward opportunities because of high comfort levels with the managements of companies in the portfolio. - Regret-aversion: Holding on to an investment you know to be sub-optimal.

EXAMPLE: A manager maintains a relatively high cash balance to lower risk, while ignoring new investment opportunities and the potential for market gains.

“Many facts of the world are due to chance… Causal explanations of chance events are inevitably wrong.”

Daniel Kahneman, Thinking Fast & Slow

LNW’s Approach

The LNW Investment Team applies behavioral finance theory in two ways:

- Evaluating the biases of the asset managers we include in client portfolios. Exploring behavioral biases is a key component of our manager due diligence process. Throughout the hundreds of meetings that we conduct with asset managers every year, we look for cognitive and emotional biases in their investment processes, security selection, sell discipline and portfolio construction. We strive to identify managers who not only understand their own biases but can take advantage of opportunities created by irrational investor behavior.

- Evaluating our own biases in choosing asset managers and establishing portfolio asset allocations. Each recommendation made by a member on LNW’s investment team undergoes extensive peer view, in which the Chief Investment Officer and other analysts are tasked with finding faulty logic and biases in the conclusions presented (in essence playing the devil’s advocate). Understanding each team member’s predisposition to certain biases improves our analysis and leads to better decisions as we position portfolios with the goal of achieving optimal levels of risk-adjusted return over a full market cycle.